In an era defined by the relentless speed of information, we are drowning in data but starving for truth. If you open any social media app, turn on any news channel, or browse the latest wellness trends, and you are immediately bombarded with claims. Some are true, some are partially true, and a great many are to use the technical term baloney (a.k.a. bullshit).

Navigating this landscape requires more than just intelligence; it requires a specific set of cognitive tools. Fortunately, the late astrophysicist and science communicator Carl Sagan provided us with exactly that. In his 1995 book, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, Sagan introduced the “Baloney Detection Kit”, a set of rules for critical thinking designed to fortify the mind against propaganda, pseudoscience, and deception.

Decades later, as deepfakes blur reality and algorithms feed our confirmation biases, Sagan’s kit is not just a philosophical curiosity; it is a survival guide for the modern mind.

Science as a Candle in the Dark

Before diving into the specific tools, it is crucial to understand the philosophy behind them. Sagan did not view science merely as a body of knowledge, a collection of facts about an animal cell or black holes. He viewed science as a way of thinking.

Sagan argued that the machinery of science, its skepticism, its demand for evidence, and its ruthless self-correction is the best defense we have against being deceived. He wrote:

"The kit is brought out as a matter of course whenever new ideas are offered for consideration. If the new idea survives examination by the tools in our kit, we grant it warm, although tentative, acceptance."

The “tentative” part is key. A baloney detector doesn’t make you a cynic who rejects everything (there is a difference between cynicism and rationalism, and in this case skepticism). It makes you a skeptic who only accepts the truth once it’s been proven.

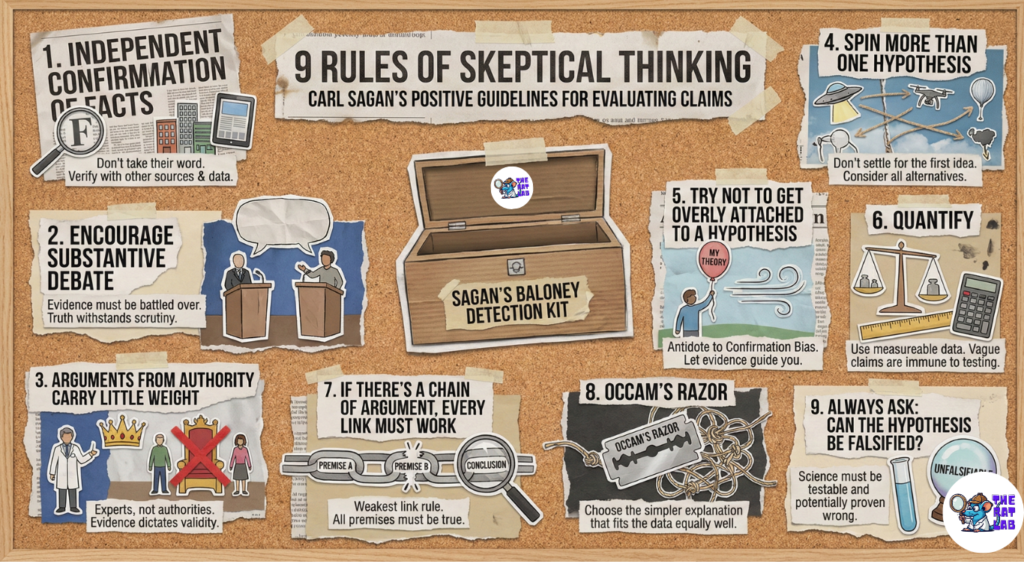

The Toolkit: 9 Rules for Critical Thinking

Sagan’s kit consists of nine primary tools for skeptical thinking. These are the positive guidelines, the things you should do when evaluating a claim.

1. Independent Confirmation of the Facts

The first rule of the kit is arguably the most important: Don’t take anyone’s word for it.

If a pharmaceutical company claims their new drug is 100% effective, or a politician claims crime has dropped by 50%, you cannot rely solely on their internal data. You must look for independent verification. Are other labs replicating the results? Do government statistics match the politician’s claim?

- In the Digital Age: This means checking the primary source. If a headline says “Study Shows Coffee Kills You,” click through to the actual study. Does the abstract actually say that? Or is the headline a distortion of a minor correlation? Was the article peer-reviewed? Was the study conducted on human beings using double-blind experimental method?

2. Encourage Substantive Debate

Evidence must be battled over. Sagan urged us to encourage substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view.

Truth is rarely found in an echo chamber. If a claim is robust, it should withstand scrutiny from its harshest critics. If an idea is protected from criticism if you are forbidden from questioning it, it is likely baloney.

3. Arguments from Authority Carry Little Weight

In science, there are no “authorities”; at most, there are experts.

“Too many such arguments have proved too painfully wrong. Authorities must prove their contentions like everybody else.“

Just because a Nobel Prize winner says something doesn’t make it true. Just because an influencer with 10 million followers endorses a crypto token doesn’t mean it’s valuable. The validity of a claim rests on the evidence, not the status of the person making it.

4. Spin More Than One Hypothesis

This is a safeguard against falling in love with your first idea. When faced with a mystery (e.g., “Why are there strange lights in the sky?”), don’t just settle on the first explanation that comes to mind (“Aliens!”).

Sagan suggests you simply think of every possible explanation:

- It could be a drone.

- It could be a satellite.

- It could be an optical illusion/camera artifact.

- It could be a military test.

Then, think of tests that could systematically disprove each of these alternatives. The hypothesis that survives this Darwinian selection process has a much better chance of being the right answer.

5. Try Not to Get Overly Attached to a Hypothesis

This is the antidote to Confirmation Bias. If you are the one who came up with a theory, you have a natural vanity to want it to be true.

Sagan advises: “Ask yourself why you like the idea. Compare it fairly with the alternatives. See if you can find reasons for rejecting it. If you don’t, others will.”

6. Quantify

If whatever you are explaining has some measure, some numerical quantity attached to it, you’ll be much better able to discriminate among competing hypotheses.

- Vague: “This policy will make the country better.”

- Quantified: “This policy will increase GDP by 2% and reduce unemployment by 0.5% over three years.”

Vague claims are immune to refutation. Quantified claims can be tested.

7. If There’s a Chain of Argument, Every Link Must Work

This is often called the “weakest link” rule. If your conclusion depends on a premise A, which leads to B, which leads to C, then A, B, and C must all be true.

If premise A is false, the entire argument collapses, no matter how logical the jump from B to C is.

8. Occam’s Razor

When you are faced with two hypotheses that explain the data equally well, choose the simpler one. If you hear a bump in the night, two hypotheses might explain it:

- Hypothesis A: The wind blew a branch against the window.

- Hypothesis B: An inter-dimensional ghost is trying to communicate via Morse code but is clumsy.

Both explain the noise. But Hypothesis B requires you to assume the existence of dimensions, ghosts, and ghost-clumsiness. Hypothesis A only requires wind and a tree. Occam’s Razor dictates you bet on the wind.

9. Always Ask: Can the Hypothesis be Falsified?

This is the distinct line between science and pseudoscience, popularized by philosopher Karl Popper.

For a claim to be scientific, there must be a way to prove it wrong. If a psychic says, “I can read minds, but only when skeptics aren’t in the room because their negative energy blocks my powers,” that claim is unfalsifiable. It cannot be tested. If you can’t test it, it’s not worth debating.

The Fallacies: What Not To Do

Sagan’s kit also includes a list of logical fallacies, i.e., errors in reasoning that manipulators use to trick you. Recognizing these is just as important as using the tools above. Here are five of the most common ones we see today:

1. Ad Hominem (“To the Man”)

Attacking the arguer rather than the argument.

- Example: “You can’t trust Dr. Ramanathan’s data on climate change because he drives a messy car.”

- Reality: Dr. Ramanathan’s hygiene has no bearing on atmospheric carbon levels.

2. Argument from Ignorance

The claim that whatever has not been proved false must be true, and vice versa.

- Example: “You can’t prove that UFOs aren’t aliens, so they must be aliens.”

- Reality: Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, nor is it proof of existence.

3. Observational Selection (Cherry Picking)

Counting the hits and forgetting the misses.

- Example: A gambler says, “I won three times in a row! I have a system!” while ignoring the previous 40 times he lost.

- Digital Context: Social media feeds are engines of observational selection, showing you only the news that confirms your worldview.

4. Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc

“It happened after, so it was caused by.”

- Example: “I drank a special tea, and then my cold went away. The tea cured my cold.”

- Reality: Colds usually go away on their own. The timing was likely coincidental.

5. Straw Man

Caricaturing a position to make it easier to attack.

- Example: “Scientists want to ban all fun because they suggest we eat less sugar.”

- Reality: The scientists likely suggested a moderate reduction for health reasons, not a totalitarian ban on “fun.”

Applying the Kit to Modern Life

Why does this matter? Because the stakes are higher than ever.

In the past, “baloney” might have meant a snake-oil salesman selling a tonic in a village square. Today, baloney can destabilize democracies, crash economies, and incite violence.

We see the violation of these rules constantly:

- Crypto Scams: Violate the rule of Independent Confirmation. They rely on hype and authority (celebrity endorsements) rather than technical audits.

- Political Polarization: Relies on Observational Selection. We only see the failures of “the other side” and the successes of “our side.”

- Conspiracy Theories: Often violate Occam’s Razor and Falsifiability. They construct massively complex webs of secrecy to explain events that are more simply explained by incompetence or chance.

The Emotional Challenge

The hardest part of the Baloney Detection Kit is not understanding the logic; it is managing the emotion.

We want to believe. We want to believe there is a simple cure for our illness, a simple investment that will make us rich, or a simple political enemy who is to blame for all our problems. Sagan’s kit asks us to do something uncomfortable: to pause, to doubt, and to ask for evidence even when the lie feels good.

Conclusion: The Democracy of the Mind

Carl Sagan wrote The Demon-Haunted World not just to teach science, but to protect democracy. He feared a world where the critical faculties of the people were eroded, making them unable to distinguish between a charismatic leader and a competent one, or between a verified fact and a fabricated outrage.

The Baloney Detection Kit is a shield. It protects your wallet from swindlers, your health from quacks, and your vote from demagogues.

Using the kit takes effort. It is easier to accept the world as it is presented to us. But as Sagan reminded us, we have a responsibility to the truth. By sharpening our skepticism, we keep the candle burning in the dark.

"If we are not able to ask skeptical questions, to interrogate those who tell us that something is true, to be skeptical of those in authority, then we are up for grabs for the next charlatan, political or religious, who comes ambling along." — Carl Sagan

📚 Recommended Reads

-

Demon Haunted World:

Science as a Candle in the Dark —

🔗 Amazon |

Amazon India

[…] language, but it is a dialect that can be spoken with a lying tongue. Keep your eyes open, your skepticism sharp, apply rational thinking and your hand on your […]

[…] Falsifiability is the unique quality of any effective scientific paradigm. […]